“Header image caption: On 23 January 1966, Soldiers of the 327th Infantry, 101st Airborne Brigade, prepare to move across a rice field in search of Viet Cong (VC). The Soldiers’ mission during Operation “Van Buren” was an effort to deny the vital rice harvest to the VC. The 327th was operating in areas around their home base located in Tuy Hoa, Republic of Vietnam.”

Photographer: PFC Robert C. Lafoon

Department of the Army Special Photo Office (DASPO)

Before reading, please note that this is a living document. As such, I will be updating it with more details about the war and to accurately reflect current historiographical trends. The goal is to keep readers better informed about the war.

Indochina

France invaded Southeast Asia in 1858. Thereafter, region by region, France imposed its rule through conquest. Five separate colonies constituted French Indochina. Three of the colonies—Cochinchina in the south, Annam in the center, and Tonkin in the north—compose modern Vietnam. The two other entities, Cambodia and Laos, followed different paths towards independence. As a colonial power, France ruled Indochina brutally, exploiting the region for resources. The Second World War brought the permanence of French rule into question.

Following France’s defeat by Germany in 1940, with Vichy approval, Japan deployed forces to French Indochina. In agreement with the Japanese, Vichy authorities administered French Indochina. That ended in in 1945 when Japanese troops wrestled control away from the Vichy administration. During this turbulent period, Hồ Chí Minh and fellow communists—the Việt Minh—waged an insurgency against the Japanese. After Japan’s surrender to the Allied Powers later that year, however, France attempted to reassert dominion over French Indochina . The Việt Minh did not go away. Instead, the Việt Minh declared an independent Vietnamese state. War with the French loomed on the horizon.

American involvement in the Vietnam War began during the age of decolonization. With the Soviet Union backing nationalist movements across the globe, the United States feared the expansion of communist influence. The U.S. pledged to confront communist revolutions under the Truman Doctrine. Between 1946 and 1954, France fought to retain its colonial holding of French Indochina against the communist, nationalist Việt Minh forces still led by Hồ Chí Minh. America assisted the French war effort with funds, arms, and advisors.

France Defeated

On the eve of the Geneva Peace Conference in 1954, Việt Minh forces under General Võ Nguyên Giáp defeated a French army at Điện Biên Phủ. A single, independent Vietnam did not emerge from Geneva as the two communist powers, the Soviet Union and China, refused to back Hồ Chí Minh fearing that doing so would escalate tensions with the U.S. The Geneva Peace Conference temporarily divided Vietnam into two separate states until UN monitored elections occurred. Elections, however, never transpired as the U.S. feared a communist victory.

Two Vietnamese states therefore emerged—the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, or North Vietnam, and the Republic of Vietnam, or South Vietnam. The U.S. helped establish South Vietnam, backing Ngô Đình Diệm, who served as Prime Minister. America viewed him favorably because, while being a nationalist, Ngô Đình Diệm was anticommunist and had lived in the U.S. Ngô Đình Diệm, however, was a Catholic in a predominately Buddhist country. His Western views often clashed with those held by other Vietnamese. In 1955, the CIA supported Ngô Đình Diệm in his bid to defeat all opposing political elements in South Vietnam.

Americanization

A series of events hampered America and South Vietnam’s early war effort. The Battle of Ap Bac in 1963 demonstrated a South Vietnam not fully prepared for the challenges of confronting an insurgency. Despite a clear numerical advantage as well as using mechanized and airborne infantry, Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) forces were mauled by People’s Liberation Armed Forces (PLAF) units. Modeled after the U.S. Army, ARVN was too technology dependent to operate without U.S. assistance. Journalists reporting on the battle criticized ARVN and Ngô Đình Diệm’s regime. Such reports caused the Kennedy Administration to send Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara and General Maxwell Taylor to assess the state of affairs in South Vietnam. While McNamara and Taylor voiced their support of Ngô Đình Diệm, U.S. Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge supported a coup against the South Vietnamese leader in 1963.

In the wake of Ngô Đình Diệm’s assassination, and the merry-go-round of subsequent military dictators, the situation in South Vietnam further deteriorated. On 2 August 1964, after extensive provocation, North Vietnamese patrol boats fired upon the USS Maddox. Two days later on 4 August, the infamous Gulf of Tonkin incident transpired with American authorities claiming a second attack against the USS Maddox. The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution emerged from this second so-called attack. This act of Congress provided Johnson with the power to defend Southeast Asia with any measures he deemed necessary. Initially, U.S. authorities intended to use units like the 173d Airborne Brigade as security for American military installations in South Vietnam. Yet before the end of 1965, the U.S. Air Force, Army, and Marines sought to bring the PLAF and People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) to battle.

The American War

Lê Duẩn, party head and leader of the Politburo, effectively controlled North Vietnam. While Hồ Chí Minh served as the public face of North Vietnam, Lê Duẩn excised unequaled power inside the nation. Indeed, his vision of how to fashion a single, Vietnamese state became that of the military. He favored the general offensive and uprising as the means of unifying all of Vietnam under Hanoi’s rule. What that meant was North Vietnam would rely on a two pronged strategy—massive PAVN operations and internal rebellion through the PLAF to destabilize the South Vietnamese government and permit the conquest of South Vietnam by Hanoi.

Search and Destroy

Under General William C. Westmoreland, head of Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), the defeat of PAVN and PLAF units existed as the legitimate top priority. MACV commenced a war of attrition meant to exact a human toll Hanoi could not bear. Commencing on 2 March 1965, U.S. Air Force and U.S. Navy aircraft began Operation Rolling Thunder, an intense bombing campaign over the skies of North Vietnam that lasted until 2 November 1968. American warplanes targeted North Vietnam’s military assets in an effort to force the government in Hanoi to abandon the war in South Vietnam and begin serious negotiations to end hostilities, thereby making a ground war unnecessary. These efforts failed, leaving the U.S. with seemingly little choice but to use American ground forces in South Vietnam. On November 14th and 15th, 1965, the Battle of the Ia Drang Valley validated Westmoreland’s search and destroy approach when elements of the 7th Cavalry Regiment defeated a numerically superior PAVN battalion in the remote hinterland of South Vietnam near the Cambodian border.

Search and destroy meant sending U.S. forces out to hunt down and bring PAVN and PLAF elements to battle. In effect, search and destroy served to spread Saigon’s authority by aiding pacification. To create a cohesive state, pacification offered Saigon the means to extract the loyalty of the people—often forcibly. Pacification laid at the heart of the U.S. strategy for the war. The use of helicopters to transport soldiers into battle, kill ratios, and not retaining the hard won ground epitomized America’s ground war.

By 1967, MACV erroneously asserted that Hanoi’s forces lacked the ability to conduct large-scale offensive operations in the central part of South Vietnam. American officials like Westmoreland and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara publicly proclaimed a communist defeat was on the horizon, while privately expressing doubts about victory. The realities in Vietnam proved an American and South Vietnamese victory as an idea only. Rather than weakened from continuous MACV offensive operations, PAVN and PLAF units actively avoided combat and prepared to laugh what Le Duan envisioned as the decisive event of the war, the General Offensive and Uprising of 1968—otherwise known as the 1968 Tết Offensive.

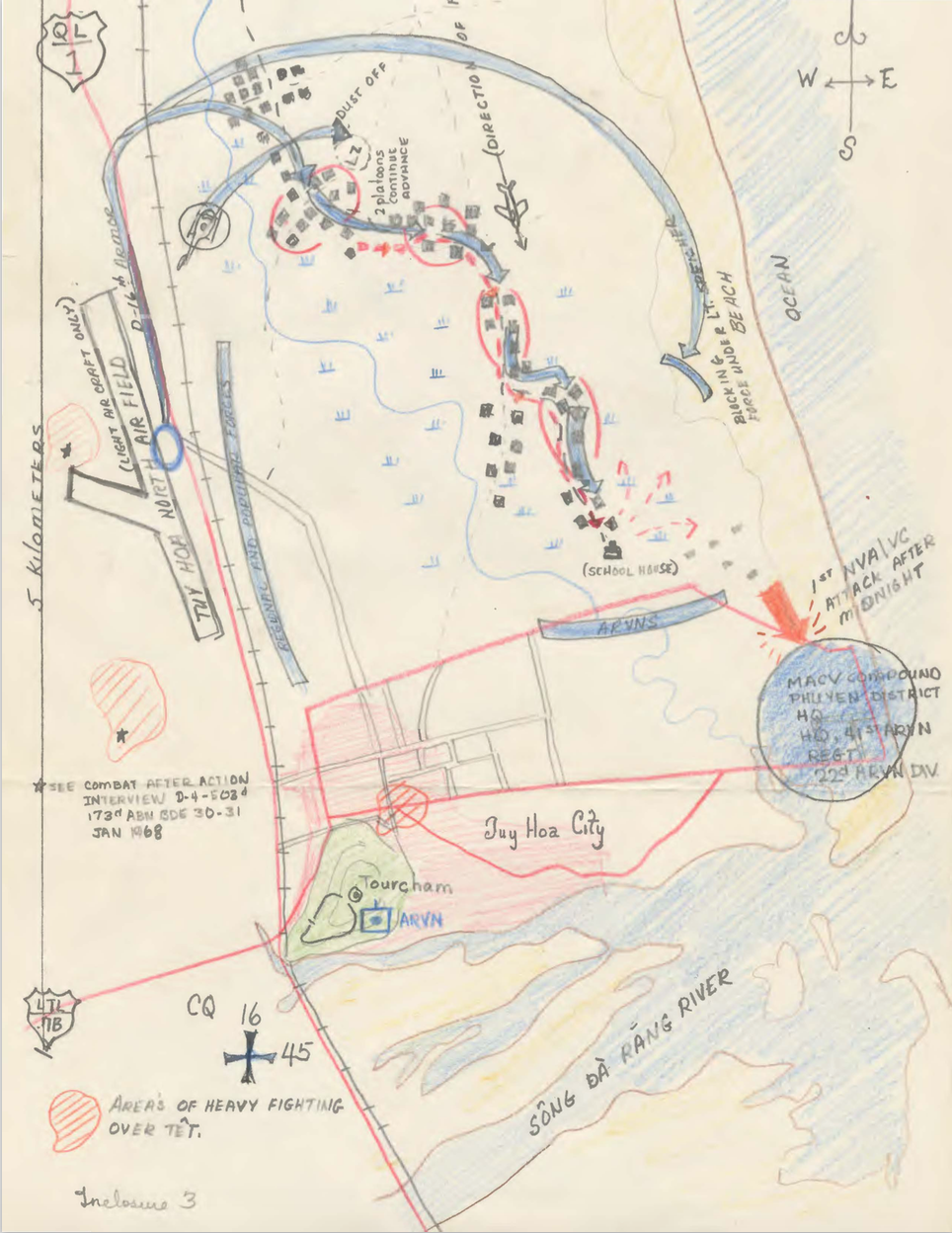

The 1968 Tết Offensive

On 30 January, during the Vietnamese lunar new year of Tết, PAVN and PLAF formations launched a massive, nationwide assault against South Vietnam’s major population centers. At places like Khe Sanh, Saigon, and Hue, epic battles reminiscent of those waged in the Second World War transpired. Indeed, in the words of President Lyndon B. Johnson, “[Communists] are, it appears, trying to make 1968 the year of decision in South Vietnam–the year that brings, if not final victory or defeat, at least a turning point in the struggle.” Yet the Communist offensive failed to topple the Saigon government. Moreover, American and South Vietnamese troops decimated the PLAF’s ranks.

The 1968 Tết Offensive was indeed the turning point in the Vietnam War. The immediate fallout from the offensive proved a public relations triumph for North Vietnam. As the first truly televised war, scenes of fighting, particularly those from Tết, fueled antiwar movements in the U.S. Images from Vietnam presented an out of control war where Americans were needlessly dying. Militarily, the offensive left communist forces shattered and in need of replenishment in both soldiers and materiel. That created the perception of permanent weakness among American authorities. Under an entity called Civil Operations and Revolutionary Development (CORDS), U.S. sponsored nation-building efforts spread rapidly across South Vietnam. Yet the communists’ response—low-intensity warfare—ensured the continuance of war.

When the most trusted news anchor in America, Walter Cronkite, declared the U.S. could not win the war, the Johnson administration knew they had lost public support. With growing antiwar sentiment after years of endless war, Johnson excused himself from the upcoming 1968 presidential election. Famously stating “With America’s sons in the fields far away, with America’s future under challenge right here at home, with our hopes and the world’s hopes for peace in the balance every day, I do not believe that I should devote an hour or a day of my time to any personal partisan causes or to any duties other than the awesome duties of this office–the Presidency of your country. Accordingly, I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your President.”

Withdrawal

In 1969, the American public learned about the Mỹ Lai Massacre of 16 March 1968. That war crime further soured public opinion of the war and contributed to the misconception that all American soldiers were murderers. In this event, U.S. Army soldiers killed unarmed South Vietnamese civilians until a US helicopter crew intervened.

After his election, President Richard Nixon and his administration sought to disengage America from the war in Vietnam. American combat forces were withdrawn from South Vietnam in a process called Vietnamization. Dubbed “victory with honor,” this process amounted to the American abandonment of South Vietnam. By this time General Creighton Abrams had replaced Westmoreland has head of MACV. Additionally, the U.S. entered into peace negotiations with the North Vietnamese. Peace talks, however, stalled as both sides refused to compromise. Hoping the absence of American ground forces would afford a quick victory for Hanoi, PAVN launched a massive assault on South Vietnam known as the 1972 Easter Offensive. Only resilient ARVN units and U.S. airpower stymied PAVN’s offensive. Consequently, secret negotiations between Hanoi and Washington resulted in the 1973 Paris Peace Accords. Omitted from negotiations, the South Vietnamese felt betrayed as the accords permitted PAVN units to occupy South Vietnamese territory. Moreover, U.S. seriously curtailed monetary and military support for Saigon. Without such assistance, the Republic of Vietnam succumbed to communist rule after North Vietnam’s 1975 invasion of the country.